The Number of Youth in Juvenile Detention in California Has Quietly Plummeted

Major portions of San Diego’s juvenile detention facilities sit empty. And it’s not just San Diego. Falling crime rates, combined with more money for prevention and a changing juvenile justice culture, have virtually emptied California’s juvenile halls.

From the Voice of San Diego

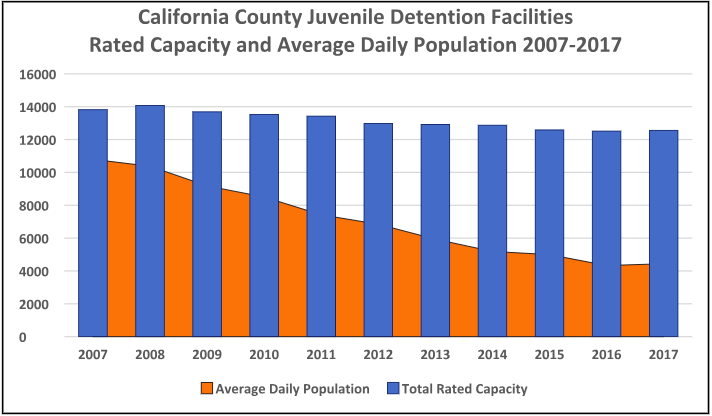

In the past decade, the number of children behind bars decreased so dramatically that in San Diego County – and across the state – juvenile halls and camps stand at unprecedented levels of emptiness.

But the tough-on-crime politicians who built many of those prisons predicted a much different outcome.

In the ‘90s, many politicians from both the left and right – former Gov. Pete Wilson was one of the most relentless; Hillary Clinton the most notable – evoked coming waves of teenage “super predators” who would not only plague America’s inner-cities, but even spill out into affluent white suburbs to sew their chaos.

No one painted this portrait so well as John Dilulio, the criminologist who popularized the term. A self-styled tough researcher, he surveyed juvenile prisons, where he saw “vacant stares and smiles” and “remorseless eyes” staring back at him. These kids “pack guns instead of lunches,” he wrote. They roam the streets in “‘wolf packs,’” and “‘maim and kill on impulse.’” He warned of a ticking “demographic crime bomb” that would soon unleash unprecedented levels of youth crime onto American streets.

But Dilulio’s crime bomb – which led to tougher laws and bigger prisons – was a dud. Crime didn’t actually go up; it plummeted, especially among juveniles. Fear of super predators gave way to an era of acknowledgment by prosecutors and judges that locking up children put society at more risk, not less. Throughout the 2000s, laws softened and more money headed toward prevention.

San Diego County’s four detention facilities can hold 855 young people. But on a recent Wednesday, just 311 youths were housed inside the county’s prisons and camps, said Chief Probation Officer Adolfo Gonzales. At least five to six wings of the county’s juvenile detention space are totally empty at present, he said. Just eight years ago, the number of incarcerated kids was three times as high: The average daily population in lockup stood at 1,008 for January 2010.

Gonzales told me about a recent example that highlights how the system has changed. A San Diego cop brought a 9-year-old boy to the Kearney Mesa juvenile hall for throwing a rock that almost hit a young girl. The girl’s parents had pressed for charges and, in the past, when a child like that was brought to juvenile hall, he’d end up in a jail cell. But now, if a case warrants it, on-call judges and probation officials will divert the child before he gets through the door. In this case, the boy ended up in a “cool bed” – a system started in 2011 that puts a child with a foster family or relative for a few days while a case manager can try to connect the kid with services instead of plugging him or her into the system.

When you put a kid like that – who is really only guilty of being a kid – into juvenile jail, he or she is far more likely to come back, Gonzales said. Gonzales himself – who spent decades working in a police force and is the former police chief of National City – is indicative of how mindsets have shifted over time. But he still receives the occasional pushback from police. “They say, ‘Oh, you’re so liberal. You’re setting them free,’” he said. “’I’m doing it different,’ I say. ‘The old way doesn’t work.’”

Undoing the old ways has been difficult. The climax of the tough-on-crime era came in 1994, when California voters passed a three-strikes law that could send a person away for life for three felonies. Then in 1997, in anticipation of the coming youth crime wave, the state began a funding push that would ultimately put $750 million into the construction of new juvenile facilities, according to data from the Commonweal Juvenile Justice Program. The final act of that period was a successful ballot initiative supported by Wilson in 2000 that made it easier for children to be tried as adults and mandated harsher sentences.

But even in the peak days of the super predator mentality, the trends that would empty out juvenile halls began to emerge. Most importantly, juvenile crime started to decrease in the mid-‘90s and still hasn’t stopped. Felonies, misdemeanors and minor infractions like curfew violation continue to tumble. Researchers don’t fully understand this trend, said Mike Males a fellow at the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice. College enrollment has steadily increased, as dropout rates have gone down, he said. Another juvenile justice expert I spoke to, Maria Ramiu at the Youth Law Center, thought the shift from latchkey kids to helicopter parents might have played a part. Academics have also suggested that abortion becoming widely available after Roe v. Wade in 1973 helped bring crime down.

In 2000, the same year that Wilson helped pass Prop. 21, the state Legislature started funneling money toward crime prevention too. Legislators allocated more than $100 million annually to programs that were alternatives to detention, like anger management or substance abuse treatment. Then in 2007, more state money brought the yearly total to roughly $300 million. Around that time, most counties’ juvenile jails and camps had been at or over-capacity for years. But soon after, incarceration rates started plummeting.

Along the way, counties have introduced their own funding streams and new practices. In recent years, all of San Diego County’s police chiefs and sheriffs have committed to new protocols that require cops to connect kids – especially low-level or first-time offenders – with service providers and case managers rather than drop them off at juvenile hall. In the Chula Vista Police Department, for instance, service providers from South Bay Community Services work side by side with police inside the station. They can assess the likelihood that a child will reoffend and recommend services or accountability programs on the spot. Cops will often end up dropping charges.

The problem for California now is what to do with all the empty space.

In the coming weeks, Gonzales will oversee the closure of Camp Barrett in Alpine, which will reduce the county’s detention capacity by 90. He also said he’s trying to find creative ways to use the space by doing the equivalent of shop classes inside one of the empty wings in Kearny Mesa juvenile hall. But California’s previous building surge still leaves much unused space. Various initiatives across the state have sought to close down juvenile halls altogether, use the space for young adult offenders, or transform it into high-end residential treatment for juveniles, said David Steinhart, director of the Commonweal Juvenile Justice Program.

For now, the empty space is a symbol for the wave of super predators that never came.