Probation Seeks To Eliminate Barriers For The Unhoused, Formerly Incarcerated

In The Observer by Genoa Barrow

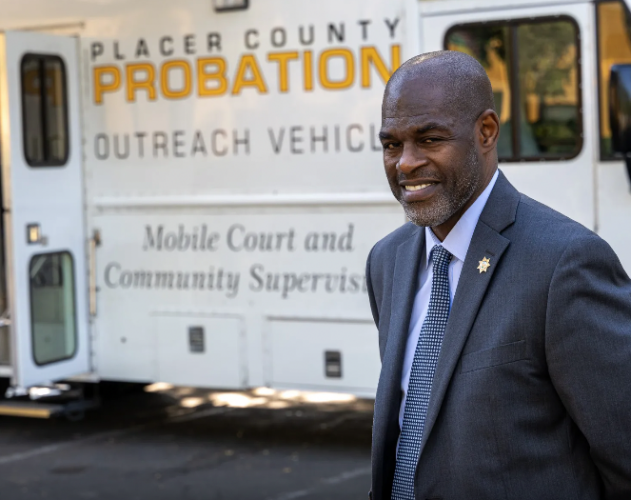

In his role as chief probation officer of Placer County, Marshall Hopper frequently gets stopped by people in the community. He often braces himself to hear something negative, as probation officers aren’t typically anyone’s favorite people.

The feedback, however, has been positive, Hopper says, from those being served by his department’s mobile outreach vehicle.

Sacramento County’s probation chief, Marlon Yarber, wants similar results. Yarber and other county officials recently announced receipt of grant money allowing them to purchase five mobile outreach vehicles of their own. The vehicles will aid the department in helping locals on probation overcome barriers that impact their ability to make mandated appointments and access other services.

Sacramento is one of 25 probation departments in California receiving grant funding in 2023. With $1.3 million, the local department got the third largest amount, behind Los Angeles County ($2.1 million) and Riverside County ($1.7 million).

While not its sole purpose, the vehicles largely will be used to reach Sacramento County’s unhoused population.

“California is facing an unprecedented homelessness crisis compounded by the fact that 70% of unhoused individuals were previously incarcerated,” says Assemblymember Tina McKinnor. McKinnor was not present for the announcement, but is backing several reform-related bills.

As of Aug. 28, 3,094 individuals on probation in Sacramento County are identified as unhoused. Of that number, 1,104 are African American. That’s 21.3% of the total number of African Americans (5,173) currently on probation in the county.

“We see this as a tremendous opportunity to actually co-deploy our teams in the health and human services departments with our partners at probation. The board has made significant investments in the county over the past couple of years, and increasing our outreach and engagement efforts and encampments in shelters and in communities that are disproportionately impacted. This is just another opportunity for us to be able to partner and get services to people where they are so that we can decrease those barriers.”

The mobile unit can bring people together with probation officers and social workers. The Placer County vehicle is equipped with TV monitors that allow for court sessions, with judges and legal representatives present virtually.

“Instead of telling them, ‘Hey, you’re going to go ride the bus for three or four hours to get to the court system,’ we bring the court system to them,” Hopper says.

Low-level offenses typically earn a person a lesser consequence.

“It’s usually four to eight hours of community service, we can oversee that,” Johnson says, adding they often have people pick up trash near the vehicle to fulfill that obligation.

“And then we move on in life instead of clogging up the court system with a bunch of missed court dates.”

People also can be linked to substance abuse treatment and housing resources.

The grant funds allow for purchase of the vehicles as well as equipment, telecommunications, and other technology needed to operate them. Yarber also envisions operating full size trucks with attached trailers to offer showers and laundry service – which will go a long way toward fostering dignity, as the inability to bathe, focus on hygiene or wash one’s clothing is another barrier to making appointments and social interaction.

Unwarranted Attention

Homeless individuals often commit low-level offenses and then end up with warrants, Johnson says.

“That warrant gets really stagnant because they can’t get to their court dates,” he explained. “When you’re living in a field, you’re not remembering that today is Thursday and that you’re supposed to be in court.”

“I typically refer to probation officers as a hybrid combination of social worker and law enforcement. They have a very unique and a very, very important mission here in Sacramento County and across the state of California, in terms of just making sure that those that have been previously incarcerated, have every opportunity to change their lives, and do so and become productive members of our communities.”

– County Supervisor Phil Serna

Having warrants can be dangerous for African Americans, Black men particularly, as they’re often used to justify stops and other interactions that are, quite frankly, unwarranted. Some of those interactions have fatal outcomes. “Driving while Black” is still a thing, as demonstrated by an October 2022 report from Catalyst California and the ACLU of Southern California that found Blacks in Sacramento County are over 4.5 times more likely to be pulled over for traffic violations than whites. Many add other words like “shopping,” “dining,” “traveling,” “breathing” and “struggling” in front of “while Black to call attention to just how pervasive racism remains nationally.

The Re-entry and Housing Coalition says homelessness can be both “a cause and consequence of having a criminal record.” According to the group, more than 25% of people experiencing homelessness report being arrested for activities that are a direct result of their homelessness, such as sitting, lying down or sleeping in public.

“By no means should anyone associate [probation’s involvement] with trying to criminalize homelessness,” County Supervisor Phil Serna says.